The faith of Solzhenitsyn, his concerns for the West, the "narcissism" debate...

...and woeful election choices.

I’m busy with a few projects that won’t be published for a while, so there may be fewer updates on published articles in the newsletter. One was released yesterday, a simple explainer on “narcissism”, why it’s such a popular topic of discussion, and whether it’s the cause of scandals in the church, among other things. It’s on Christian Today here.

Perhaps I will try a new purpose for this newsletter that is close to my heart: a place to discuss forgotten books. I am a voracious reader with a serious second hand book addiction, and always scour ebay for interesting books priced at £3. Sometimes the books I find are rubbish. More often than not, they’re fascinating, and give me an angle and information that is a bit different to the norm.

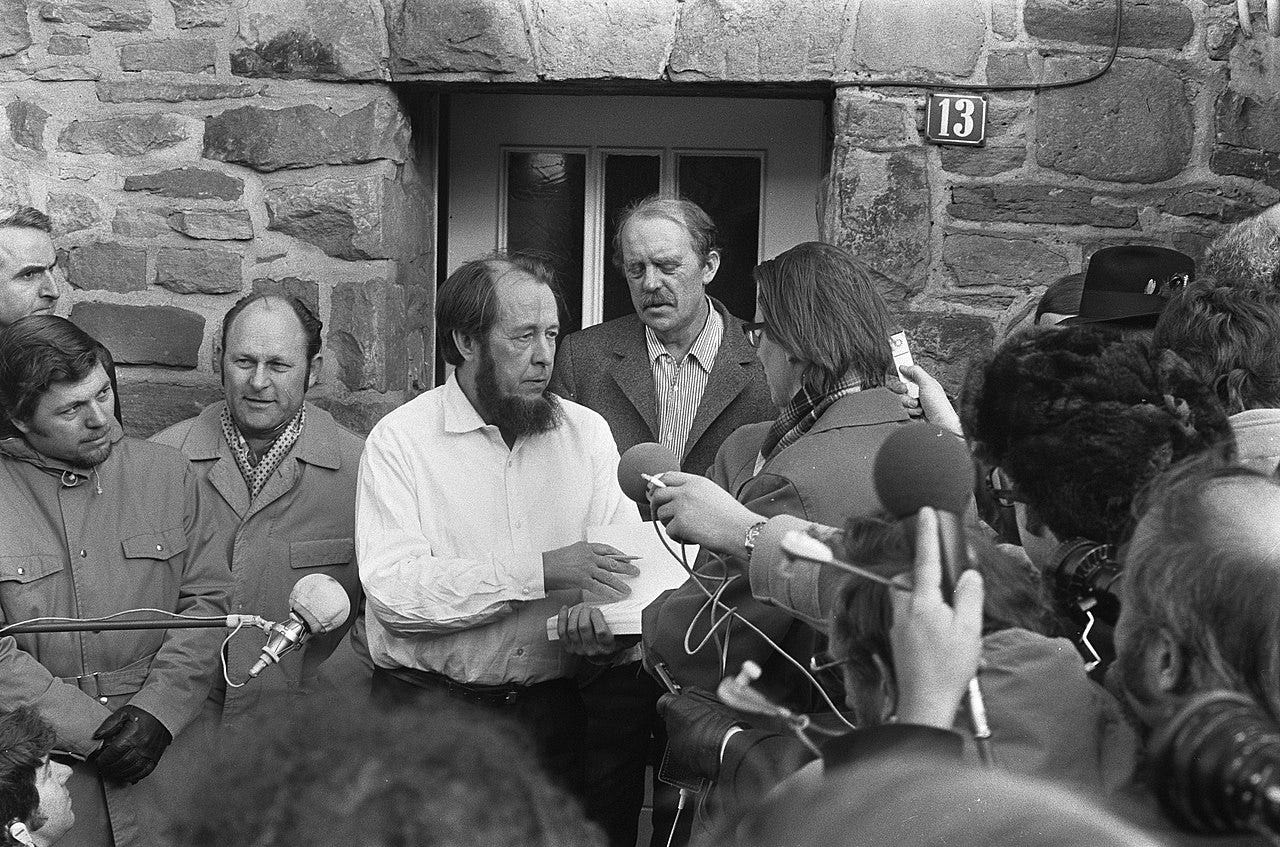

Solzhenitsyn: a soul in exile

I’ve just finished reading Joseph Pearce’s biography of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, an author that I had not thought about much until the emergence of Jordan Peterson some years ago, who discusses his work regularly. I had perceived the writer as just a thoughtful literary type who wrote of his bad experiences in Soviet prison camps, but he’s much more interesting than that. As the biography tells, it was Solzhenitsyn’s brave work - he could easily have been killed or imprisoned again for what he wrote - that educated the West about the horrors of Soviet Russia. Until then, hard to believe as it is, there were many public “intellectuals” who were favourable towards communism and even Stalinism. To their credit many of them renounced this naive support once the truth became known. What would Solzhenitsyn say of the recent increase in support of and interest in Marxism, even Stalinism, despite all the evidence of its bloodthirsty insanity?

Solzhenitsyn’s critiques of both communist Russia - and the decadent West he observed when he was forced into exile in the 1970s - are relevant to us today. Especially as we face extremely unappealing electoral choices on both sides of the Atlantic. Here in the UK, the two main options of political party for the general election on July 4th (Conservative and Labour, for the non Brits!) are unappealing to almost everyone. The very unconservative Conservatives perhaps represent the amoral West that Solzhenitsyn describes, while the radical, progressive Labour Party seems to have certain echoes of late communist Russia, if not its more brutal and cruel early days. (For recent commentary on Labour’s alarming authoritarian or radical tendencies, see the Daily Sceptic article, “Keir Starmer’s Coming Revolution is More Radical Than His Opponents Realise”, or Niall Gooch’s Spectator piece, or

’s profile in Compact here.)The parents of Solzhenitsyn’s generation were religious. As he grew up the State successfully indoctrinated him against these traditions and into confident atheistic Marxism, for which he was a true believer at first. Despite this, he fell foul of Stalinist Russia due to a few flippant criticisms of the great tyrant in private correspondence with a friend, and ended up in a gulag. The biography describes this process as the arrogant true believer gradually had his delusions about Marxism, and himself, toppled through the cruelty and suffering of the camps. Others responded to these indignities with passive “psychological surrender”, but he perceived that he was lucky that his experiences revealed the truth about communism and brought him to faith:

“He even learned to be grateful to the Gulag, confessing that, along, with his time in the army, the most important event 'would be the arrest’. He went so far as to describe it as the second 'defining moment' of his life, crucial 'because it allowed me to understand Soviet reality in its entirety and not merely the one-sided view I had of it previous to the arrest'. He then reiterated what had been taken away from him by his youth in the Soviet Union, most notably the ‘Christian spirit' of his childhood. If he had not been arrested, he could only imagine with 'horror ... what kind of emptiness awaited me. The gaol returned all that to me.’ ...

Yet the tragic end was really only the beginning. It was the crucifixion preceding the resurrection, labour pains preceding birth. The arrest was the real beginning of the Passion Play of Solzhenitsyn's life, in which the pride and selfishness of his former self were stripped away like unwanted garments.”

The Russian writer developed a preoccupation with spiritual growth and living a simple, unmaterialistic life. His views would evolve, but clearly influenced by orthodox Christian ethics, he became as concerned about the selfish materialism of the West as the authoritarianism of Russia:

“Scarcely did the liberal intelligentsia in the West Suspect that Solzhenitsyn, far from being a champion of Western values, was as little enamoured of capitalist consumerism as he was of communist totalitarianism. His own views were still developing at this time, but they sprang from Russian tradition and had little in common with the materialism which was in the ascendancy in Europe and the United States. Rooted in the spiritual struggles in the camps, Solzhenitsyn's central belief was in selfless self-limitation as opposed to the selfish gratification of needless wants. As he watched Russians gorging them selves on gadgets and other consumer goods, taking their lead from the West, he felt a sense of nausea. This was not what life was about.”

Criticism of Solzhenitsyn grew in his time in exile in Europe and then the USA. His fans included fellow Christian convert Malcolm Muggeridge, who wrote:

"To fulfil the media's requirements, [Solzhenitsyn] should have felt liberated when, as an enforced exile, he found himself living amidst the squalid lawlessness and libertinism that in the Western world passes for freedom. What amazing perceptiveness on his part to have realized straight away, as he did, that the true cause of the West's decline and fall was precisely the loss of a sense of the distinction between good and evil, and so of any moral order in the universe, without which no order at all, individual or collective, is attainable.

"So, instead of pleasing the media by saluting the newfound Land of the Free, Solzhenitsyn sees Western man as sleepwalking into the selfsame servitude that in the Soviet Union has been imposed by force.... On campuses and the TV screen, in the newspapers and the magazines, often from the pulpits even, the message is being proclaimed - that Man is now in charge of his own destiny and capable of creating a kingdom of heaven on earth in accordance with his own specifications, without any need for a God to worship or a Saviour to redeem him or a Holy Spirit to exalt him. How truly extraordinary that the most powerful and prophetic voice exploding this fantasy, Solzhenitsyn's, should come from the very heart of godlessness and materialism after more than sixty years of the most intense and thoroughgoing indoctrination in the opposite direction ever attempted."

Solzhenitsyn’s greater understanding of our woes can be explained if there is a Truth, and an objective moral value to the universe, which both he and Muggeridge had come to believe, and shaped the lens they viewed the world.

Most of these events happened before my time on this Earth, but his critique is no less relevant. The moral vacuum from the loss of Christianity in the West has consequences even worse than Solzhenitsyn predicted, as new Christian convert

has begun to articulate well. She argues for a return to the faith that once made the West great; and perhaps, the late writer might have said, Russia too.The biography was written in 1999, some years before the Russian author died. Reading books before the advent of wokism and before the internet took hold is a little like a window into a forgotten world, although only 25 years ago. As they are less clouded by the increasing moral confusion of today, perhaps they can help us to a greater understanding of our problems and possible solutions?